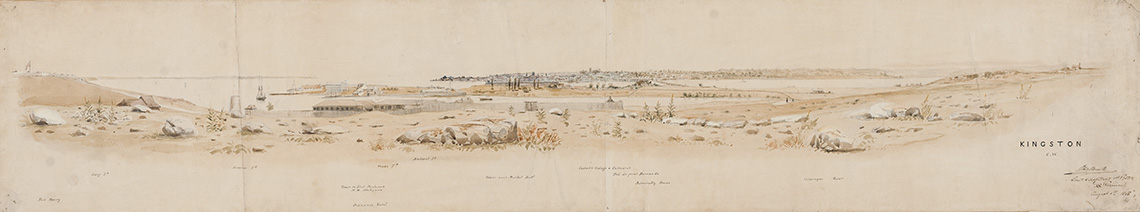

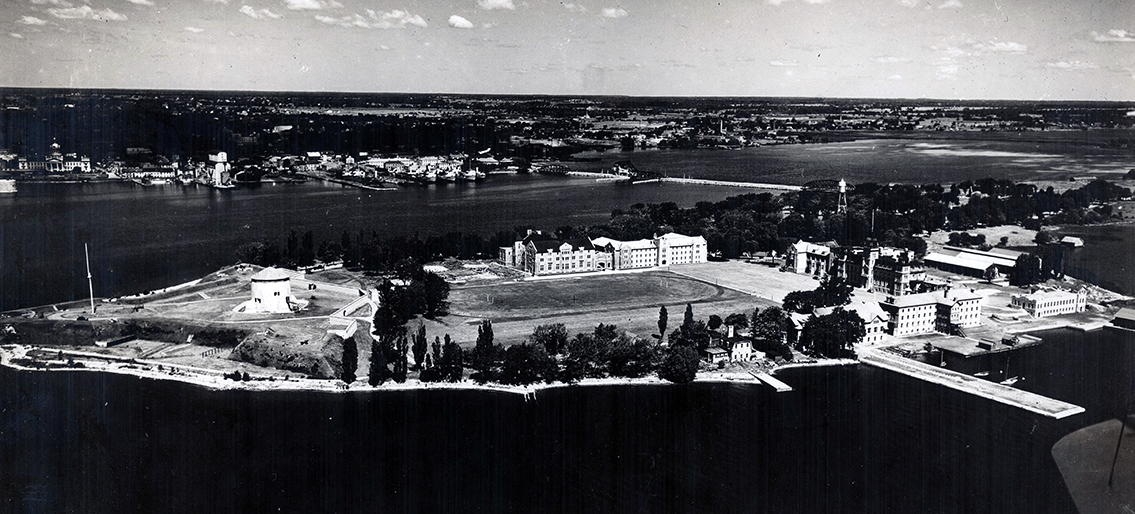

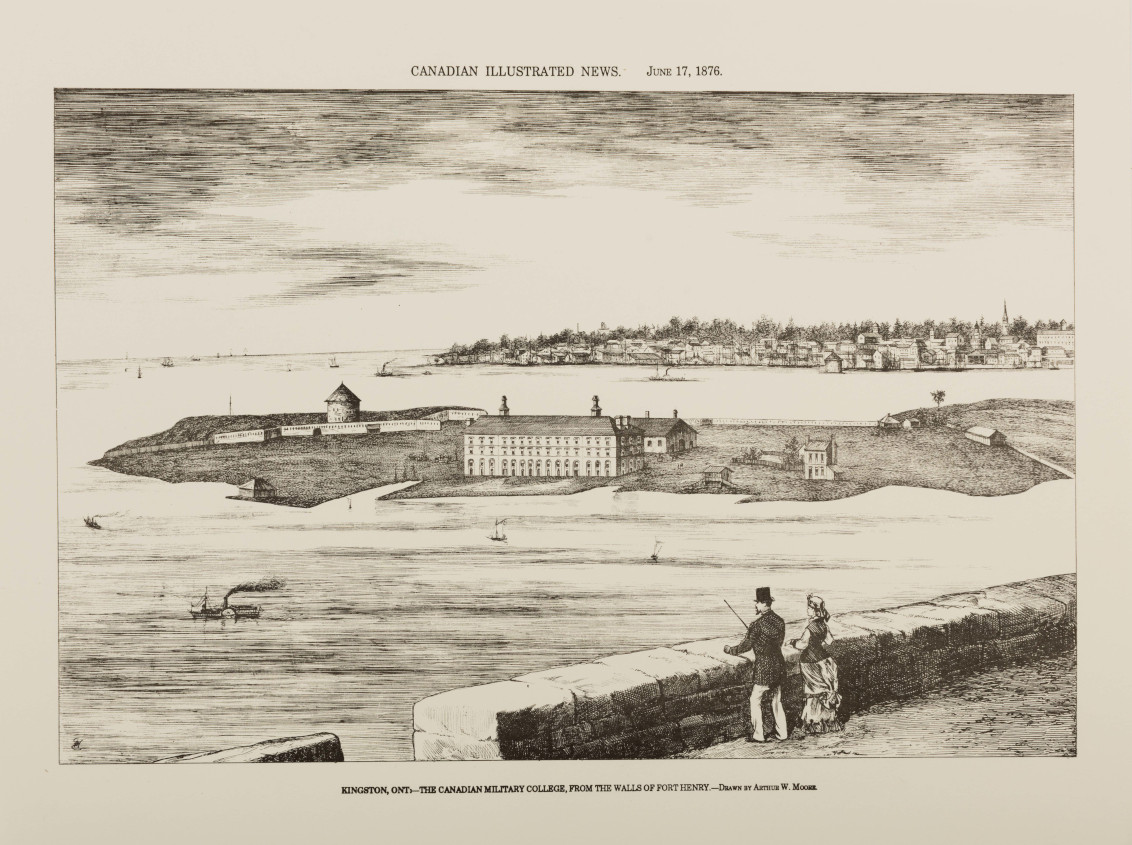

The Royal Military College is situated on Point Frederick, a small peninsula just to the east of the City of Kingston, Ontario. The Point is named after General Sir Frederick Haldimand, the Governor of Quebec from 1777 to 1786. This scenic location, at the junction of Lake Ontario and the St. Lawrence River, is one of great historic importance.

Explore the links below to discover the history and significance of Point Frederick and the Royal Military College.

Historical Overview of Point Frederick and RMC

Hunting and Fishing on Point Frederick

Archaeological site surveys and analysis of archaeological material found on Point Frederick show that Indigenous Peoples inhabited and used the Point from the Late Archaic Period through to the Middle Woodland Period (1500 BC to 1000 AD).

Prehistoric postholes and hunting artifacts located at what would have been the narrowest part of the peninsula suggest that Indigenous Peoples used the peninsula for hunting, specifically for driving deer out to the end of the point where they could be killed more easily. In a separate area prehistoric artifacts were found which indicate that a seasonal fishing camp existed on Point Frederick. The diversity of artefact material suggests that the camp was likely used by a variety of different groups of Indigenous Peoples for different reasons over a long period of time.

Provincial Marine

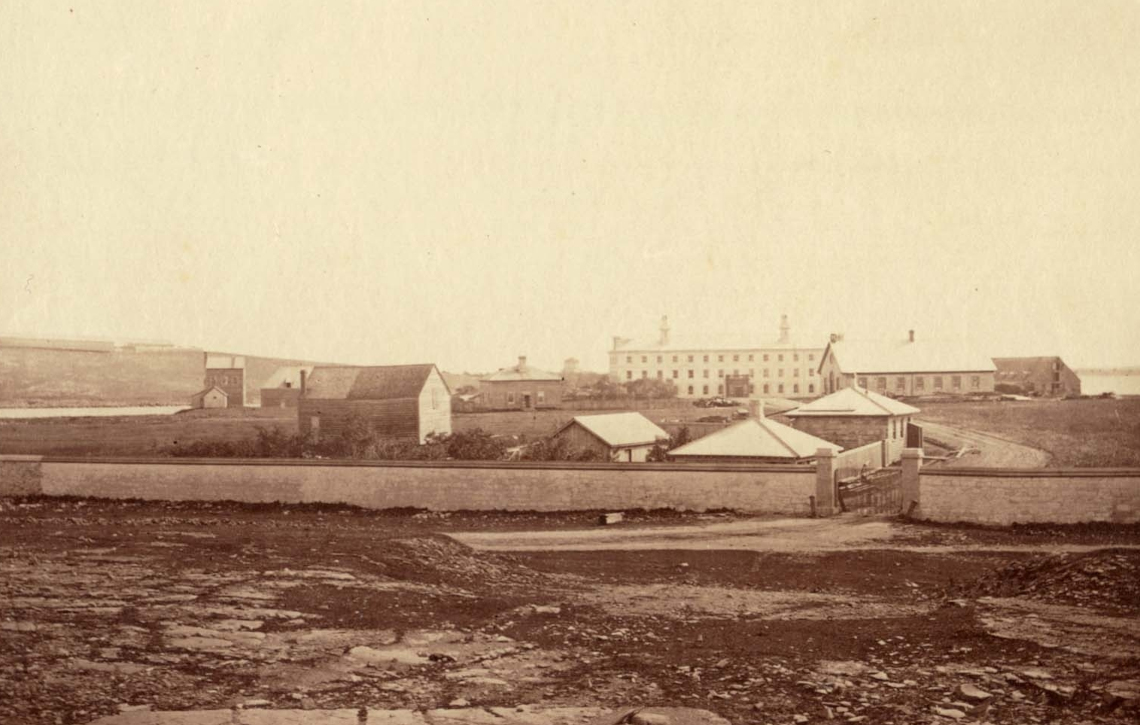

At the end of the American Revolutionary War, Carleton Island, along with its naval station and dockyard transferred to the United States of America, leaving Britain without a naval station on Lake Ontario. In 1783, Governor-General Frederick Haldimand ordered the establishment of a new post at Cataraqui (later Kingston). The Provincial Marine relocated to Point Frederick in 1789 and became an active supply depot, dockyard and trans-shipment point for the British. When the United States of America declared war on Great Britain in June, 1812, the Provincial Marine responded by attacking Sacket’s Harbor, New York . The attack was unsuccessful and the following May, the Royal Navy took command of the dockyard at Point Frederick.

Royal Naval Dockyard

As the war progressed, the facilities at Point Frederick, now under the control of the Royal Navy, were vigorously expanded to fortify the peninsula. A blockhouse, earthen ramparts, guardhouses and barracks, were developed in support of the battery to form the first Fort Frederick. By the conclusion of hostilities in 1815, 6 warships, including the first-rate HMS St. Lawrence, and numerous gunboats had been built in the naval yard.

Over a period of time following the War of 1812, as British Colonial policy and relations between Great Britain and the United States fluctuated, the military and naval facilities in the Kingston area were strengthened and continued to expand. The Rideau Canal was built to provide a safe logistic link from Montreal to the Dockyard. Fort Henry was rebuilt in stone, as were several dockyard buildings and somewhat later, a series of Martello Towers were built along the Kingston shoreline, including the Fort Frederick Tower, to augment Kingston’s harbour defences. The Dockyard, operating at reduced capacity since the Rush-Bagot Treaty of 1817, was permanently closed in 1853.

Establishment of the Royal Military College

When Great Britain began to withdraw its military support from Canada in 1870, Canada did not yet have its own permanent military. Members of the new government of Canada recognized a need for a Canadian military college but the majority of believed the civilian militia was sufficient for Canada’s defence.

In 1874, the Dominion Government of the Honourable Alexander Mackenzie was able to gain enough support in both the Liberal and Conservative parties to pass an Act to establish a Military College “for the purpose of imparting a complete education in all branches of military tactics, fortification, engineering and general scientific knowledge in subjects connected with and necessary to a thorough knowledge of the military profession.” The government emphasisedthat graduates, trained as engineers would usefulness for nation building, in an attempt to defuse political opposition to the concept of a military college.

The new Commandant of the College, Lt-Col (later Lt-Gen) E.O. Hewett of the Royal Engineers welcomed the first class of eighteen cadets, the Old Eighteen, in June of 1876. Lt-Col Hewett served as Commandant for eleven years and set many of the traditions and regulations for the College- some of which are still in place to this day. He chose the College motto, “Truth, Duty, Valour” and designed the first College Coat of Arms which is still used today.

By the time the College opened, Canada had a small standing army, but it provided limited positions as commissioned officers. The British Army, however, offered at least four commissions each year to graduates and these were eagerly sought after by those interested in an Imperial military career. Most graduates returned to a civilian profession, and saw service in the Militia where openings existed.

The Early Years

The early years of the college were stormy. The College opened with only one building for the service of Cadets, the Stone Frigate, a leftover storage building from the days of the Royal Naval Dockyard, converted to barracks and classrooms for the new College. Overcrowding in the Stone Frigate was an almost immediate problem, only slightly relieved by the opening of the new education building, later named Mackenzie Building in 1878. Col. Hewett was concerned by the lack of infrastructure and issues such as poor drainage and access to clean water, which led to illness amongst the Cadets and staff.

The representation of both French and English was also an early concern. Complaints were raised as early as 1878 that French Canadians were not equally represented among the Cadets. Some minor changes were made to address the issue but the College did not fully incorporate second language training until the 1970s.

By 1888, the College was in a general state of decline. The War Office felt the quality of RMC graduates had fallen. It was believed that there was too little emphasis on military training and that some of the professors were poor instructors. In 1896, a new Commandant, Colonel G.C. Kitson was appointed and immediately began making changes. He dismissed civilian staff, shortened the course from four to three years and raised the standards of discipline.

By the end of the South African War in 1902, it had become clear that the nature of war was changing and that Canada would have to professionalize its military in order to defend itself in the new environment. Major building projects were completed during this period and the number of cadets increased dramatically. Cadets were required to attend militia training camps and there was an expectation that graduates would accept commissions in the Canadian Permanent Force, the Active Militia or the Imperial Forces.

RMC in the War Years 1914-1945

Throughout the First World War, RMC continued to operate as a cadet college. The College program was reduced to a maximum of two years and more military training was added. Young boys were taken in and given as much education and training as possible and then commissioned and sent on active service as soon as they were of age.

In 1919, Major-General Sir Archibald Macdonell (RMC 1883-1886) was selected as Commandant of RMC. An Ex-Cadet (number 151), who had earned seven medals of distinction during the War, he was deeply respected by those he had led in battle. Macdonell re-introduced the traditional scarlet cadet uniform and reinstated the pre-war four-year academic program. New College Colours were also presented to RMC while he was Commandant.The College began to grow in both size and purpose and was now seen as the place to be for young men to receive an education.

When the Second World War was declared in 1939 the rhythm of the College continued but plans were made for the future. Similar to the Great War, courses for cadets already at the College were shortened and graduating cadets were commissioned as officers for service. However, in 1942 the College changed significantly. On June 20th, RMC’s cadet program ended. For the remainder of the War the College buildings and facilities were used for other military training, such as a two year Royal Canadian Navy training course, staff courses and intelligence training.

The New RMC 1948-1995

Following the Second World War, the fate of the College was unclear. There was significant political and financial pressure to keep the College closed. However, many Ex-Cadets and military personnel were in support of its reopening. In September, 1945, the issue was raised in the House of Commons and it was decided that the College would reopen as one of the new Canadian Services Colleges which were renamed the Canadian Military Colleges in 1968.

The Colleges were tri-service military colleges that trained cadets from all three branches of the Armed Forces; Army, Navy and Air Force. This change came as a direct consequence of the recent experience of the Canadian military in the War. It was clear that all three branches of the Armed Forces were equally important during the Second World War and success often depended on collaboration. Originally two Canadian Services Colleges were opened, RMC in Kingston and Royal Roads Military College in Esquimalt, British Columbia. A third, Le Collège militaire royale, opened in Saint Jean Sur Richelieu, Quebec in 1952.

The reopening of RMC as a tri-service college was followed by many significant changes: in 1952, the Regular Officer Training Programme was introduced which offered subsidized education in exchange for a period of obligatory service in the forces; in 1959, the College achieved degree granting status as a university in the Province of Ontario and in 1980 the first women were enrolled. In 1995, with the closure of Royal Roads Military College and Le Collège militaire royale, RMC once again became Canada’s only military college that educated and trained junior officers.

RMC Today and its Legacy

Since 1995, RMC has continued to change to meet the needs of the Canadian Armed Forces. Since it opened in 1876, the College has provided a broad based education combined with military training. The original programme, which offered instruction "in all branches of military tactics, fortification, engineering and general scientific knowledge" has now evolved into that of a modern, bilingual university offering degree programmes in Arts, Science and Engineering at the undergraduate, graduate and post-graduate levels. No longer just a Cadet school, the Royal Military College of Canada is now an important national institution and a university for the whole Canadian Armed Forces.

From the first class of graduates in 1880, Ex-Cadets of RMC have distinguished themselves in many areas of both civilian and military careers. They have seen military service in the North-West Campaign of 1885, in the South African War, on the North-West Frontier of India, in the First and Second World Wars and in Korea. More recently, Ex-Cadets have participated prominently in Canada’s peace-keeping and peace-making commitments worldwide – serving with NATO forces in Europe, in the Middle East, South-West Asia and Afghanistan, Africa, the former Yugoslavia, in Eastern and Central Europe and even in Space. Many Ex-Cadets have also served in government, academic, business and professional spheres, as the civilian nation-builders of the original concept.

The Old Eighteen and New Hundred

Introduction

The Royal Military College of Canada was established in 1876 out of a necessity for the Dominion of Canada to train civilians as military officers. The College not only trained cadets to military excellence but also provided for an equally high standard of academic distinction for students choosing a civilian career. The College rapidly gained both international reputation and favour with the Canadian populace.

The two pioneering classes of 1876 and 1948 were each significant: the class of 1876 because it was the first class of the newly established military college and the class of 1948 because it was the first class entering the new tri-service Canadian Services College.

The class of 1876 had eighteen students, known as the “Old Eighteen” and the class which entered the College in 1948 had one hundred students and was called the “New Hundred”.

Why RMC was established

In 1870 and 1871, Great Britain recalled its Forces from the Colonies. Canada did not have its own permanent military and greatly depended on the British Army for its defence and military training. In 1815, a discussion by the Assembly of Lower Canada resulted in a proposal for a military college. Unfortunately, religious and racial differences caused the project to collapse.

In 1816, Captain A.G. Douglas also suggested that a college should be created which would be independent from the Assembly thus allowing the college to be free from religious, political and mercantile controversies. He hoped bringing in recruits from different parties and affiliations would help in unifying the Canadian populace. These recommendations were not seriously considered until the British troops stationed in Canada were recalled to Britain.

Establishing the Military College

The vast majority of Canadians were not interested in military matters and believed the economic cost of establishing and maintaining a military college was too high. To gain enough political weight to see the project through Prime Minister Honourable Alexander Mackenzie obtained bipartisan support from both the Liberal and Conservative parties. It was well recognized at its inception that a military college would be watched and considered closely both by supporters and critics. It had two objectives: to produce a high standard of officers qualified as engineers, cavalry, artillery and infantry, and to provide education for a civilian life if a graduate chose not to pursue a military career. Prime Minister Mackenzie hoped that the establishment of the College would become an important part of nation building for the Country.

At its outset the College was not well known across the Country, providing for a small pool of candidates. The entrance examination was difficult and only eight candidates passed. A second entrance examination was posted and once again passed only eight. Two more were accepted into the program at a later date giving a total of eighteen cadets for the very first class instead of the originally proposed twenty-two.

The Old Eighteen

The Old Eighteen did not have previous military experience and did not truly understand what military life meant. For example, A.B. Perry had only seen one military parade on July 1st, 1867 when he was eight-years-old. He had only known one army officer whom he met when he was six years old and the rest of his military knowledge came from the stories about the British Army in Blackwood’s Magazine.

On June 1st, 1876, between 10 in the morning and noon, the new cadets reported to Point Frederick. No special ceremony was held for the opening of the College; Prime Minister Mackenzie would not visit until six weeks later. Only the College staff and students were on the grounds that day. In that first month the cadets were fitted for their uniforms and taught the essentials of military housekeeping such as making beds, folding uniforms and how to pipe-clay buckskin belts, equipment and rifle slings so they looked snow white.

- A.G.G. Wurtele

- H.C. Freer

- H.E. Wise

- W.M. Davis

- T.L. Reed

- S.J.A. Denison

- L.H. Irving

- F. Davis

- C.A. Des Brisay

- V.B. Rivers

- J. Spelman

- C.O. Fairbank

- A.B. Perry

- J.B. Cochrane

- F.J. Dixon

- G.E. Perley

- H.W. Keefer

- D. MacPherson

New Hundred

September of 1939 saw the beginning of the Second World War; in 1942 the Royal Military College closed as a cadet college and was used instead for officer staff training. Third and fourth year students at the College were given commissions right away, while the first and second year students continued classes until they were given commission in the late spring of 1940.

Shortly after the end of the Second World War, in September of 1945, the re-opening of the Royal Military College was raised in the House of Commons. It was decided that the College would become a tri-service college thereby training cadets from all three branches of the Armed Forces; Army, Navy and Air Force. This came as a direct consequence of the recent experiences of the Canadian Military in the War. It was clear that all three branches of the Armed Forces were equally important during World War II and success often depended on collaboration.

The Royal Military College welcomed one hundred new students on September 8th, 1948 with Brigadier D.R. Agnew acting as the new Commandant of the College. Two years later students from Royal Roads Military College in Victoria, B.C. (1940-1995) joined the College in their third year to fulfill the school’s tri-service mandate.

Support for the College Openings in 1876 and 1948

Old Eighteen

Canadians were not interested in military matters and the House of Commons was hesitant in planning because of the expense of financing the College. Buildings needed repairs or to be repurposed, and staff needed to be hired and paid. Finding staff for the College proved extremely difficult. The War Office, in Great Britain, refused to allow for officers to receive full regimental pay when not on the British active list. British Officers also were unenthusiastic to work with a colonial government clearly uninterested in military matters.

The Ex-Cadet Club members, including A.B. Perry (RMC 1876-1880), were staunch supporters of the re-opening of RMC. Here, Perry meets W.D. Hargraft (RMC 1948-1952) at the 1948 reopening.

New Hundred

Not everyone was convinced that the Royal Military College should be re-instated as a college; however the College had many ex-cadets and military personnel who supported its re-opening. The Kingston Whig Standard added support in an editorial printed on February 23rd, 1946. Using statistics, the Whig claimed that the Royal Military College had provided a strong nucleus of high quality officers in all the wars in which Canada had participated.

Life at RMC

Old Eighteen

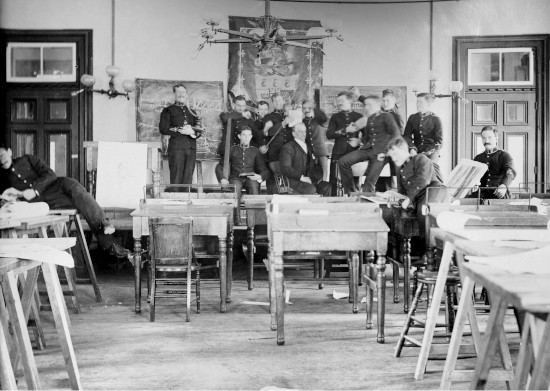

In the beginning the courses were fluid and under development; as new classes were admitted to the College, Colonel Hewett introduced new courses. Compulsory courses consisted of: mathematics, including plane trigonometry and practical mechanics; fortifications; artillery; military drawing; reconnaissance and surveying; military history; administration; law; strategy and tactics; French or German; drawing; drills; military exercises; and discipline. New courses that were introduced included: descriptive geometry; geology which alternated between chemistry or electricity; gymnastics; and equitation.

Sports at the Royal Military College flourished quite early on and the College quickly gained a good reputation for its athletic ability.

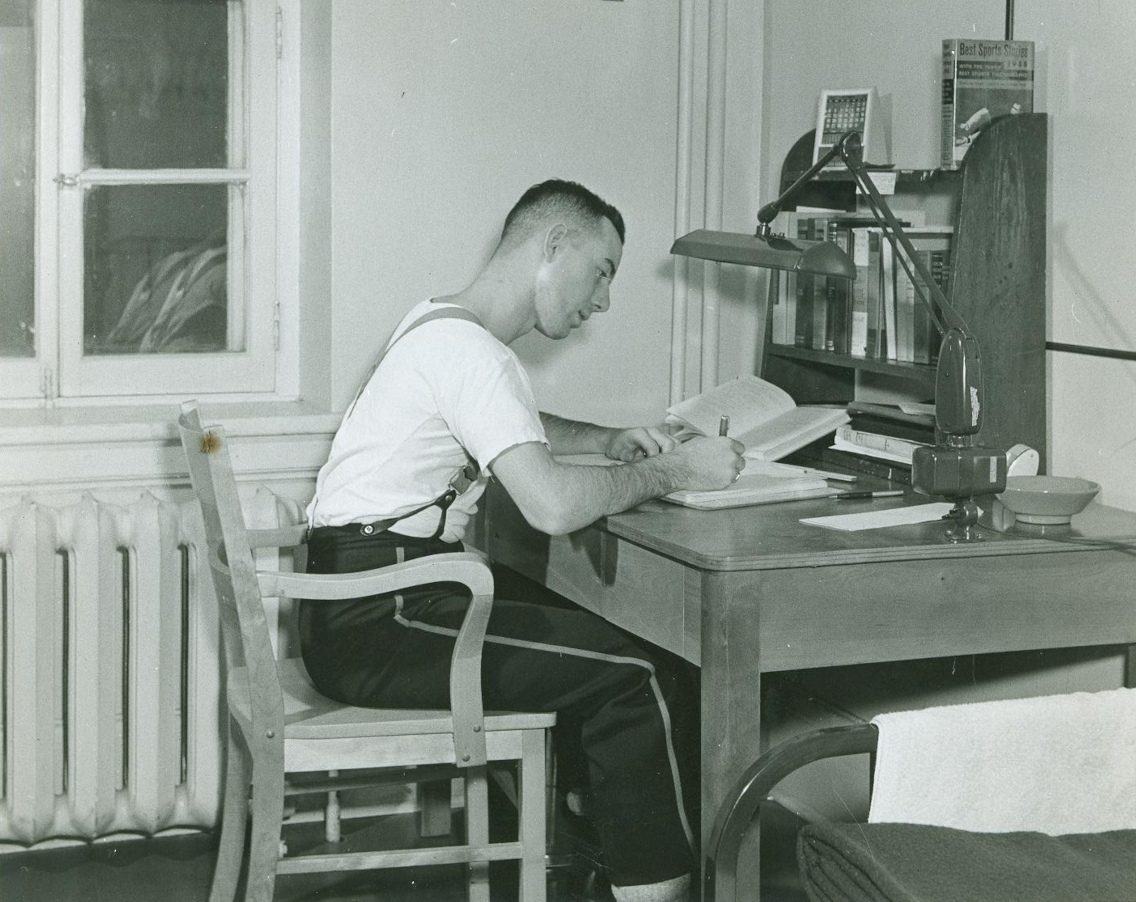

New Hundred

The college curriculum for first and second year cadets included: military studies; English; French; history; mathematics; physics; chemistry; engineering drawing; and descriptive geometry. In his third year each cadet could choose between a general arts course or engineering. If a cadet chose the general arts he then elected five arts courses with a major and minor in addition to military studies. If engineering was chosen the cadets specialized in the civil, mechanical, electrical or chemical branches.

With the re-opening of the cadet college extracurricular activities that had been practiced before the War were brought back, such as the Recruit Obstacle Race, the Harrier Race and Copper Sunday. The West Point hockey series was also resumed along with an expanded sports programme and more opportunities for intercollegiate games. The June ball was also revived.

Standards and discipline

Old Eighteen

At first discipline was administered lightly although Cadets still felt the pinch of restraint compared to what they were used to in their civilian lives. Cadets were not allowed to leave the college until they had their uniforms and then, only when a hostess invited them out. A month after the College opened Colonel Hewett directed that the severity of discipline increase. The regulations that gave civil and military professors power of arrest and officers the power to impose two days extra drill was enforced. The Commandant could impose up to fifty-six hours of solitary confinement.

New Hundred

Disciplinary rules were kept to the same standard followed by cadets of the old college. Cadets and College staff took part in more social and cultural events than they previously had and the social interactions were much less formal. There were some growing pains with the integration of the Royal Roads cadets who entered the Royal Military College in their third year. When commands were rotated after a couple months many of the cadet officers from Royal Roads were given greater responsibility. During this integration, some of the Royal Military College students complained that the discipline had become more rigid and did not follow The Royal Military College’s method of discipline wherein the recipient of an order must understand its purpose. Such growing pains were quickly resolved between the groups and a cohesive environment was achieved.

Life after RMC

Old Eighteen

Of the eighteen students who made up the first class at the Royal Military College five of the students served at one time or another in either the Canadian or British armed forces. The remaining thirteen held predominantly civilian careers. Two became presidents of engineering firms; another became a superintendent of the Nevada School of Industry. Four years after graduating two of the Old Eighteen class members created the Royal Military College Club, S.J.A. Denison who became the first Club Secretary and L.H. Irving who was the first Club President. The RMC Club’s inauguration was on March 15th, 1884.

New Hundred

When the New Hundred graduated in 1952, Canada was involved in the Korean War, and the military sent all College graduates immediately to theatre for active service. Some believed that the heavy focus on academic programming would mean the weakening of the old military spirit and efficiency, however, the success of the graduates in Korea quickly ended these concerns. Lieutenants D.G. Loomis (RMC 1948-1952); H.C. Pitts (RMC 1948-1952); A.M. King (RMC 1948-1952); and C.D. Carter (RMC 1948-1952); were awarded the Military Cross.

Conclusion

At its inception, the Royal Military College of Canada was a vague concept garnering little national support. After several decades of successfully graduating numerous classes of officers following its dual purpose education mandate, the Nation began to view the College with a sense of pride. In 1959, RMC became legally able to grant degrees and today offers B.A., B.Sc., engineering degrees as well as honours and graduate programs. This was followed by another important milestone in 1980 when women were admitted to the College. The Royal Military College has been an important part of Canadian history since it was established in 1876 and has continued to produce graduates with high standard of military excellence.

Mackenzie Building

Early Years at the Royal Military College

The idea of establishing a military college in Canada began as early as 1815, but the official decision to create one was not made until 1874. The vast majority of Canadians were not interested in military matters and believed the economic cost of establishing and maintaining a military college was too high. Prior to Canadian Confederation Canadians had relied on Great Britain for its defense and military training and believed the current militia was sufficient. Prime Minister Alexander Mackenzie recognized the need for trained officers and engineers for the development of the newly independent Canada and campaigned for the establishment of a Canadian Military College.

By June 1st 1876 the first class - known as the Old Eighteen, were welcomed to the college grounds. The Old Eighteen had very little to no experience with the military. However, these new recruits, along with their superiors quickly picked up the expectations of a military college including polished uniforms and daily drills. In the first few years the College grew slowly. There was a lack of faith from Canadians, and the War Office felt the quality of Cadets the College was turning out was in decline. However, by the late 1890’s into the early 1900’s the college began to dramatically shift with a new, stricter Commandant, major building projects to expand the campus and an increase of entries to the College.

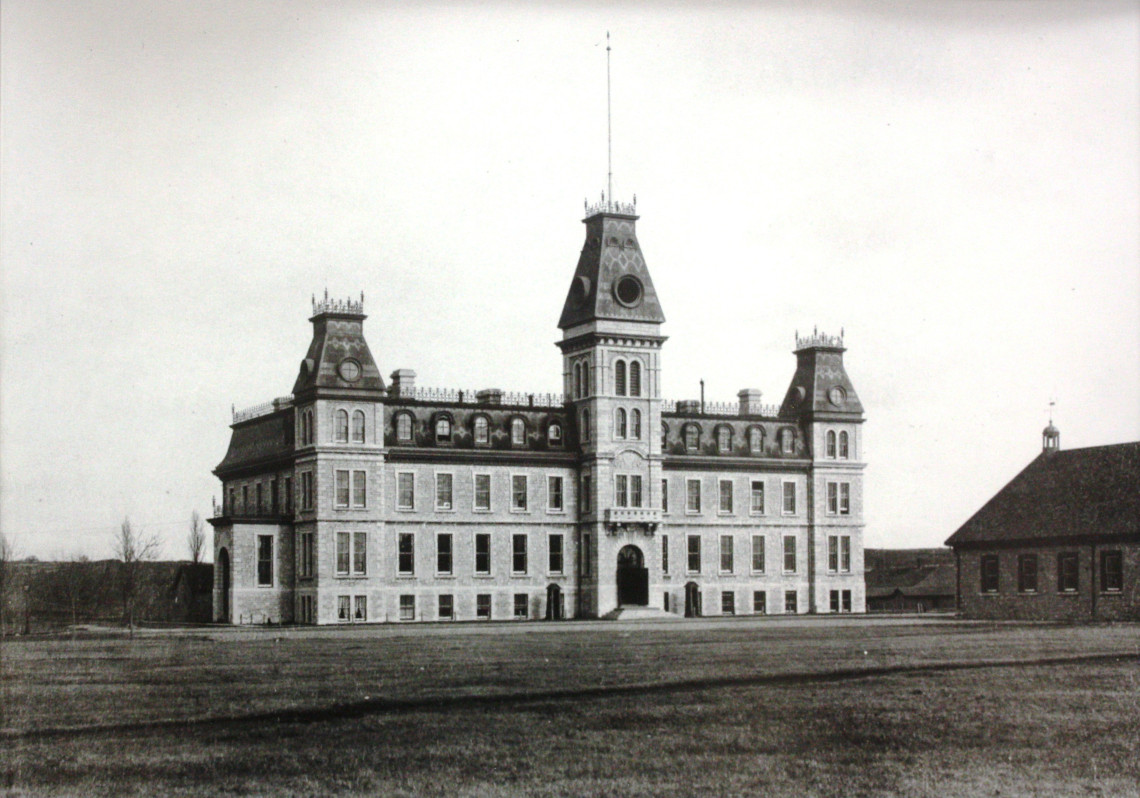

Mackenzie Building

The Royal Military College opened to the first class of eighteen cadets with only one building for the service of the College, the Stone Frigate. By 1877, the Stone Frigate which housed the barracks, classrooms, dining hall, kitchen and sick bay, was unsurprisingly overcrowded. Colonel E.O. Hewitt, the first Commandant of the College, was concerned by the lack of infrastructure and pushed for construction of new buildings to accommodate for the College’s growth. A new Educational and Mess Block to the north of the parade square had been part of the original 1875 construction plan but the approval to build it was not given until April 1877. Construction on the Educational Block began that summer and was completed by June 1878. The new Educational Block would house the Library, classrooms, a kitchen, a Cadet dining hall, and administrative offices- such as the Commandant's Office, which is the only room that has retained its original function. The construction of the new Educational Block, freed-up much needed space in the Stone Frigate for cadet and staff accommodation. The Educational Block was the first expansion of the college and to this day remains a centerpiece of the college grounds. It would later be named Mackenzie Building after Prime Minister Alexander Mackenzie.

The Architecture of Mackenzie Building

The Educational Block, or Mackenzie Building, is one of the most recognizable buildings at the Royal Military College because of its distinct architecture. The Building reflects the Second Empire, or Mansard style, that became popular in Canada in the 1870s. Often used on educational and institutional buildings, it was intended to give a strong dignified presence and exude character. Similar examples include the Parliament Buildings in Quebec and Montreal City Hall.

Construction on the Educational Block began in 1877 by the Department of Public Works under the supervision of chief architect Thomas Scott. The drawings and construction were overseen by local Kingston architect Robert Gage, who favoured the Second Empire style.

Mackenzie Building is characteristic of the Second Empire style with its mansard roof, symmetrical massing (or layout), tall central tower, dormer windows, large rounded front door and a unique roofline that is emphasized by cast iron work and classically detailed stone chimneys. Inside the central tower the main entrance is decorated with elaborate stucco work, groined (or double barrel vault) ceilings, and Corinthian capitals. The main hallways were decorated with high ceilings, three-foot high wooden wainscoting, elaborate woodwork and a magnificent double staircase which sits in the center of the building. Upon its completion the building was outfitted with modern luxuries such as bell pulls and food elevators for a total final cost of $45,475.

The End of the Old Educational Block?

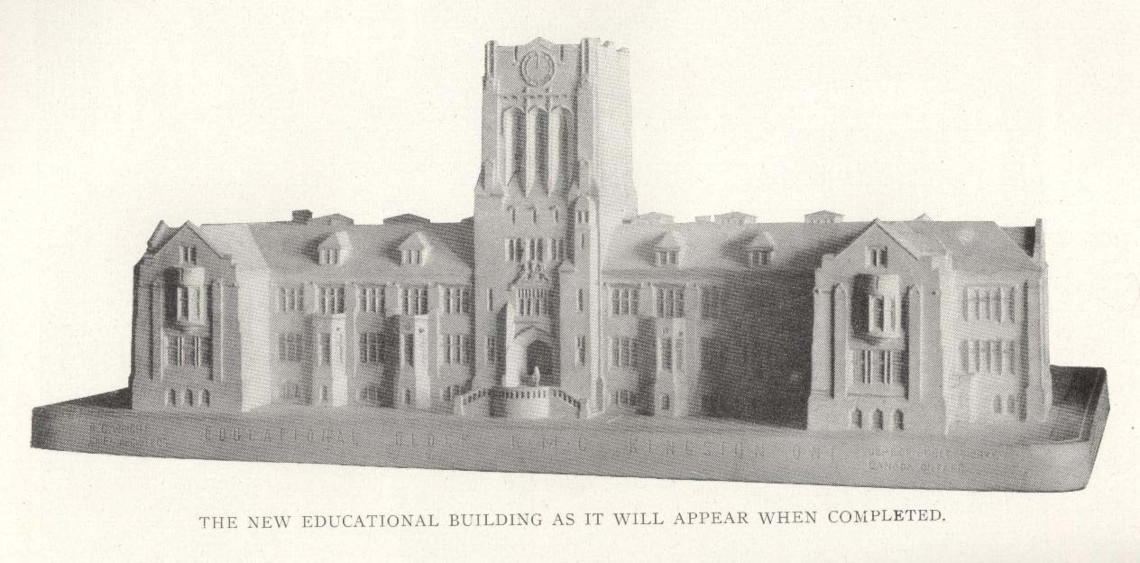

Following the First World War, Lieutenant General Sir Archibald Cameron Macdonell (RMC 1883-1886) assumed the appointment of Commandant of the Royal Military College and his arrival corresponded with the expansion of the College facilities. Macdonell’s predecessors had been arguing the need for a new, modern academic building to accommodate the growing cadet wing and finally in 1917 the government approved. The Public Works Department decided it would be more cost-effective to tear down the old and out of date Mackenzie Building and replace it with a new more modern academic building. This new academic building became known as the New Educational Building.

Because of limited funding and the need to continue using Mackenzie Building during construction, the new building would be built in two phases. After the West Wing of the new academic building was completed in 1921, no additional funds were available to tear down Mackenzie Building and construct the East Wing. Military spending was reduced following the War and the military college was an easy target. Eventually Mackenzie Building was modernized and then connected to of the new Educational Building. Merging the two buildings led to the strange architectural silhouette of the Old and New Educational Buildings that still mystifies members of the RMC community and visitors to the college today.

Memorials were added to both buildings to commemorate those who had served during the War. Mackenzie Building’s main staircase became a memorial to graduates of the College that have died in service. In the new Educational Building, known today as Currie Building, an assembly hall was built as a tribute to the Canadian Corps that served in the First World War under the command of Sir Arthur Currie.

Fire! At the Old Educational Block

From its construction, Mackenzie Building has been a prominent architectural feature on Point Frederick. Mackenzie Building has also been the place of some incredible once in a lifetime moments. Captured in a dramatic photograph, the clock tower was struck by lightning in August 1991. Both the Canadian Forces and Kingston Fire departments responded to the blaze which took more than an hour to extinguish. Fortunately, the fire was contained in the top of the tower leaving most of the rest of the building unharmed.

That was not the first time Mackenzie Building had caught fire. The first major documented fire in Mackenzie Building occurred on May 12th, 1931 for a total cost of $40,000 in damages. This fire severely damaged the top west wing and upper Mess Room, while the remainder of the wing and the central portion of the building were affected by water and smoke. The most significant loss was that of the library in the top south west corner. Nearly half of the collection of books was lost. The fire allowed for new more modern additions to be added to the building such as a new larger purpose-built library, as well as ‘splendid’ new reading rooms and day rooms for the cadets. A second fire took place in the 1970’s which was caused by an explosion in the clock tower.

Modern Mackenzie Building

Mackenzie Building was the first structure to be built for the purpose of the College and the training of military and civil engineers in Canada. One of many college expansions, it was initially the solution to an overcrowding problem in the early college years. The building has been classified as a Federal Heritage Building because of its historical connections and distinct architectural style. Since 1878, the building has been updated with a variety of modern advancements to suit the needs of the College while retaining its original design and interior plan. Mackenzie Building has hosted the social and intellectual elite of Kingston, held traditional College events such as the June Ball, and been associated with events of national significance, such as the design of the Canadian Flag. Today, Mackenzie Building is the Administrative core of the College. The Commandant and his staff work out of Mackenzie Building, along with the Principal, Registrar, and other administrative wings. Mackenzie Building embodies the founding of the College and stands as a symbol to the lasting legacy of the Royal Military College.

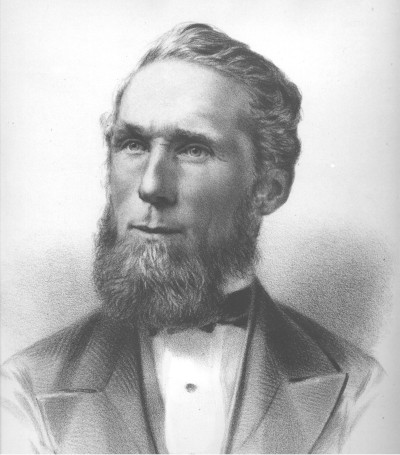

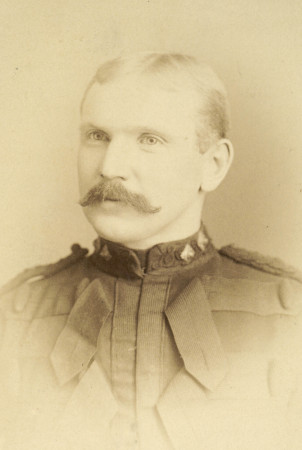

Lieutenant General Sir Archibald Cameron Macdonell K.C.B., C.M.G., D.S.O., LL.D.

Lieutenant General Macdonell was known as a leader with a hot temper, a generous heart and reckless courage in the face of the enemy, earning him the nickname of “Fighting Mac” or “Batty Mac”.

Graduating from RMC in 1886 as a Cadet CSM, an outstanding athlete, he was commissioned into the Royal Artillery, but did not take up his appointment. He joined the School of Mounted Infantry in 1888, then exchanging his commission with one in the North West Mounted Police where he served for 16 years, during which he served in the South African War with the 2nd Canadian Mounted Rifles where he earned a DSO for bravery under fire.

Returning to the Army, he became commanding officer of the Lord Strathcona’s Horse (Royal Canadians) from 1907-1910 and again from 1912-1915, leaving to become Commander of the 7th Brigade, and after Vimy Ridge, Commander of 1st Canadian Division.

Macdonell's Legacy

In July 1919, he was asked to defer retirement to become the first Canadian Military Officer to become the Commandant of RMC, serving until 1925. Macdonell had a vision that RMC was to be the best institution to develop and shape the future leadership of the Canadian Army. He had great plans and lofty goals to cultivate and expand the college to build its future.

During his tenure at RMC, Macdonell restored scarlet full dress, expanded campus accommodations for the growing number of Cadets, changed the entrance exams to the more common provincial enrollment exam, and reinstituted Staff College Preparatory and Refresher Courses as well as the Long Course for Militia qualifications. He also restored Fort Frederick, installed the flagstaff in the Fort, named the roads of the College, and opened a Museum and Recruit recreation area in the Fort Frederick Martello Tower.

Macdonell’s Accomplishments at RMC

1919 - Received the first Stand of Colours, and built the Holt Rink

1920 – Formally approved the RMC Coat-of-Arms, started work on the Memorial Staircase, instituted the Van der Smissen Award and created The Review

1921 – Opened the New Educational Building; Currie Building

1922 - Opened Currie Hall, and replaced the three-year educational program (from 1897) with four

1923 - Instituted the International Hockey Match with USMA, West Point

1924 - Unveiled the Memorial Arch

The Memorial Staircase

Major-General Macdonell established the Memorial Staircase in the 1921-22 academic year. The staircase was intended to memorialize Cadets and Ex-Cadets of the college who died in training or on active service. Macdonell added the photographs of each of the one hundred and seventy Ex-Cadets who had died during and before the First World War along the walls of the staircase, which has been maintained and is still updated today. In 1981, three stained glass windows were installed as memorials dedicated to the memory of three cadets who drowned in 1903 and the summer of 1913.

The intention of the Memorial Staircase was to instill upon the Cadets, College faculty, staff and visitors to the College the heroic sacrifice of those Cadets who died on service and to serve as a lasting memorial to cadets who sacrificed for their country.

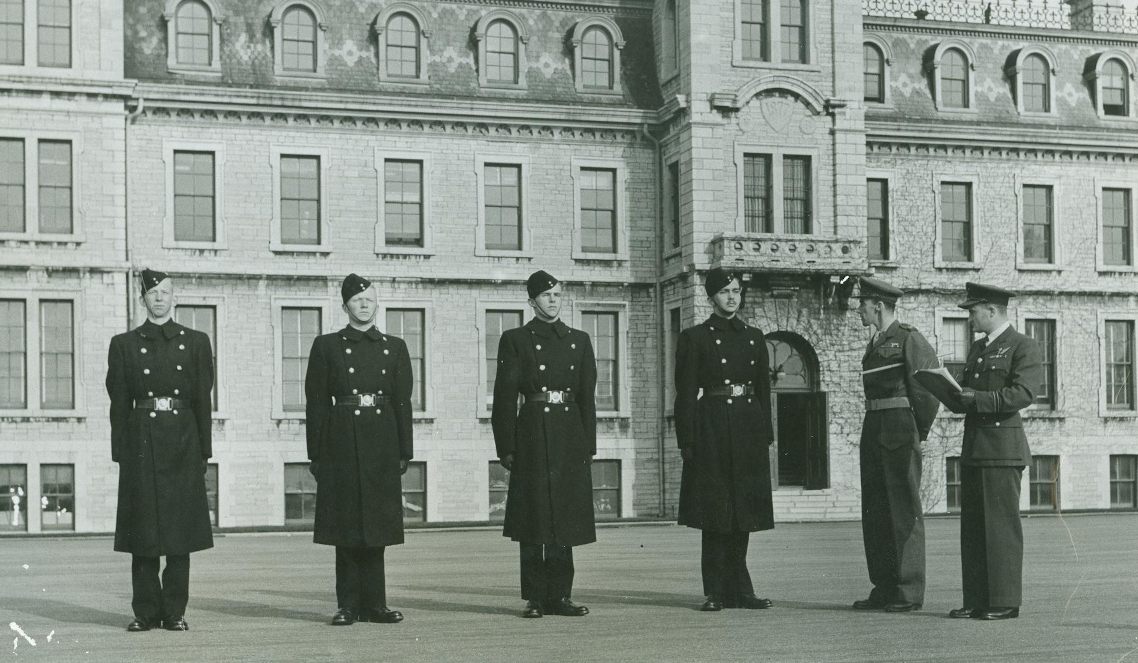

The First Stand of Colours

His Royal Highness The Prince Edward, Prince of Wales presented RMC’s first stand of colours to the college during his visit to Canada to thank the Dominion for its significant contributions during the War. General Macdonell and Prince Edward served together during the War when the Prince was the Liaison Officer for Headquarters, 1st Division that was under the command of the General. An invitation was arranged and agreed upon by both parties and the Commandant had the King’s, and the College Colours made in Ottawa. The Prince presented the Colours on 25 October 1919 to the Cadet Battalion followed by a formal address to the parade and an inspection of the Cadets.

The Colours were carried at the College until 1942 when RMC was closed as a Cadet College for the duration of the Second War. The Colours were placed for safekeeping in St George’s Cathedral in Kingston, where they remain on display today.

The Victor Van der Smissen Award

The primary Awards earned in the 1920s were the Sword of Honour and the Academic Gold, Silver and Bronze Medals. To these, General Macdonell added a new Award, named after Captain Victor Van der Smissen (RMC 1911-1914), who was killed in action on 13 June 1916 at Mount Sorrel, in Belgium.

The Award was to “be made annually to the best all-round Gentleman Cadet, morally, intellectually, and physically, who graduates at the Royal Military College of Canada, taking a commission…“which was determined by a vote of the Cadets themselves, choosing the ‘most distinguished’ Cadet at the College.

The Battalion Sergeant-Major (BSM) of the Cadet Battalion was not eligible – nor is the Cadet Wing Commander (CWC) of the Honour Slate today. The Commandant could veto the choice, but could not substitute his own selection – in 1924, there was no award as the Commandant would not accept the Cadet vote.

The Award consists of a cheque and a bound, illustrated history of Van der Smissen, presented for many years by his sister, Mrs G.L. Ridout. After the Second War, the award was renamed to include her son, No. 2415 Major W.L. Ridout, a Ghurka who was killed in Malaya in December 1941

The first Cadet to win the Van der Smissen Award was CSM #1353 HA McDougall.

International Hockey

The West Point and RMC hockey game is the longest standing international hockey rivalry to date. General Macdonell and General Douglas MacArthur, Superintendent of West Point, shared an interest in athletic competitions and organized the series. The first match was set for February 3, 1923 at the United States Military Academy. RMC won the inaugural game 3-0.

Initially the Superintendent could not promise a return game, however, the following year West Point cadets came to play in Kingston. The 1924 hockey game between RMC and West Point was the first time that the West Point cadets traveled internationally in uniform and the first time that West Point played as the away team.

Although there have been a few interruptions in its history, the game continues each year and rotates between RMC and USMA.

RMC Coat of Arms

The first Commandant, Colonel Hewett, designed RMC’s Coat of Arms around 1878. Its first known formal use is on the Certificate of Graduation for the first cadet, A.G.G. Wurtele. The full Coat-of-Arms, surmounted by a ribbon containing the Motto and supported by another ribbon showing “Royal Military College Canada” appears in the upper right hand corner on the certificate. It is dated 30 June 1880, and the shows the signatures of Captain J.B.Ridout, Staff Adjutant, and Colonel Hewett, Commandant.

The Coat of Arms and symbols derived from it were used for forty years, without formal approval. Major-General Macdonell appealed to the Prince of Wales for its approval, which was given on 21 July 1920 by His Majesty King George V. As a special mark of Royal favour, thought to be in recognition of the wartime service of Ex-Cadets, the King approved the rare inclusion of the Union Flag in the Arms.

Currie Hall: A Memorial to the Canadian Corps

Constructed in the new education building, Currie Hall was made as a memorial to the Canadian Corps and their role during the Great War. The concept of the Memorial was described by General Macdonell as a testament to Canadiansim and the triumph of the Canadian Corps. The hall was intended to remind those in it of the strength and sacrifices of Canadians in the Great War for generations to come and inspire future Cadets.

The Hall was formally opened on 17 May 1922. Designed by Major Percy Nobbs and Ramsay Traquair of the McGill School of Architecture, the hall included the badges and distinguishing patches of all the units that made up the Canadian Corps, which were painted by Major Duncan Forbes. The portraits of the Commanders were added to the hall and were painted by Canadians – Josph Rawbon and Sir Edmund Grier. The hall has been used for many events at RMC since its opening including; dances, graduation ceremonies, weddings and many more.

The Memorial Arch

In 1919, the RMC Club undertook to raise the $65,000 needed to build a memorial to the 152 Ex-Cadets killed in the Great War, including 11 other Ex-Cadets who had died earlier on Imperial Service. Designed by John M Lyle of Toronto, the Arch is hollow, built of buff Indiana limestone on a base of Quebec granite. Two brass plaques show the original names.

At General Macdonell’s invitation, HE Field Marshal The Viscount Byng of Vimy, Commander of the Canadian Corps at Vimy Ridge, laid the cornerstone on 25 June, 1932. Mrs. Joshua Wright, Silver Cross Mother of two Ex-Cadets, Maj GB Wright (RMC 1900-1903), DSO, RCE and his brother, Maj JS Wright (RMC 1908-1911), 50th Bn CEF (Gordon Highlanders of Canada) presented the Arch on 15 June 1924. The Arch served as the formal entrance to the College until the late 1970’s.

"Bill & Alfie": An Unusual War Memorial at the Royal Military College of Canada (RMC)

by Ross McKenzie, RMC Museum Curator Emeritus.

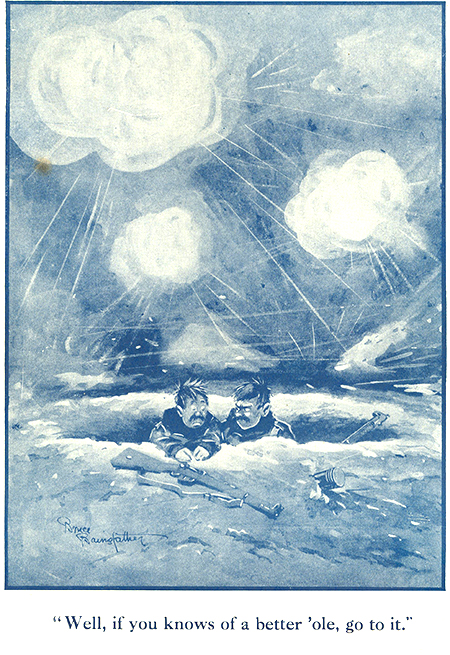

The last, and the most unusual, Great War memorial was added to the College. Two bosses (i.e. gargoyle-like) heads depicting the cartoon characters Old Bill and Alfie were placed over the side door of Yeo Hall, the newly constructed Cadet Dining Hall. Old Bill and Alfie were two of the several cartoon characters created during the War by Captain Bruce Bairnsfather, Royal Warwickshire Regiment.

For Canadians the First World War (or The Great War as it was known) began in August 1914. The heaviest fighting ended November 11th, 1918, with the Armistice with Germany, but for Canada, the War itself didn't actually end until mid-1919 when the Canadian troops serving with the Allied Intervention Force in Russia were withdrawn.

It is estimated that, in all, the Great War claimed 17 million dead and 20 million wounded, making it the deadliest conflict in human history. Canada suffered near 61,000 dead and 172,000 wounded. This brutal and hard fought conflict left not only men broken in mind and body but inflicted deep psychological wounds on the psyche of the Nation. In the immediate post-war period, all across Canada, this angst and grief found expression, in part, by the creation of thousands of memorials to honour the fallen. Along with the grief there was also a great sense of pride in the accomplishments of the Canadian soldier. The battlefield at Vimy Ridge may not have been the literal, "birthplace of the Canadian Nation," but pride in Canada's wartime accomplishments certainly increased Canadian patriotism and spurred our political evolution to independence within the British Empire.

Ex-cadets of the Royal Military College of Canada played a prominent role in the Great War, serving with both Canadian and other British Empire forces in every theatre-of-war. Although the pre-war output of the College was relatively small (RMC output was geared to the needs of the tiny, pre-war Regular army and militia: a conflict on the scale of the Great War was inconceivable) ex-cadets played a prominent role in the War. When the First Canadian Division went overseas, 22% of its commanders and staff officers were ex-cadets, and by the Armistice, the percentage of RMC ex-cadets among the whole CEF was 23%. Some 147, or just over 10% of ex-cadets serving, were Killed-in-Action.

In 1936, an officer cadet leans against the door frame into what would become Yeo Hall. You can see Old Bill just over his left shoulder.

In 1936, an officer cadet leans against the door frame into what would become Yeo Hall. You can see Old Bill just over his left shoulder.In the immediate post-war era RMC built memorials to the fallen and established other commemorative sites. Street names and geographical features on the College grounds were renamed for significant battles; the Class of 1910 planted eight birch trees in memory of eight classmates killed; the new auditorium, dedicated in 1922 as the Sir Arthur Currie Hall, was decorated to commemorate the service of the Canadian Corps and the College War Memorial - the Memorial Arch, was officially unveiled in 1924.

A decade later, the last, and the most unusual, Great War memorial was added to the College. Two bosses (i.e. gargoyle-like) heads depicting the cartoon characters Old Bill and Alfie were placed over the side door of Yeo Hall, the newly constructed Cadet Dining Hall. Old Bill and Alfie were two of the several cartoon characters created during the War by Captain Bruce Bairnsfather, Royal Warwickshire Regiment. These characters represented 'everyman' -the scruffy, but rock solid, front-line soldiers who, "coped with everything the enemy, their NCO's, their officers or the Staff could throw at them." They were universally known and beloved (except perhaps by senior staff officers whom Bairnsfather often satirized). Popular with both troops at the front and civilians at home, Bairnsfather's drawings were an important factor in maintaining morale. The caption of his most famous cartoon, "Well, if you knows a better 'ole go to it," became the catch phrase of a generation.

Why Old Bill and Alfie found their way to RMC is unknown, but presumably the Commandant of the day was a fan (every RMC Commandant from 1919 to 1945 was a veteran of the Great War). A small officers' mess was tucked into a back corner of the second floor of this newly built Cadet Dining Hall. The stairs leading up to the Mess were accessed by the side entrance decorated with the two famous heads and the bar was called, "Bill and Alfie's". The RMC Officers' Mess was relocated long ago, but the original bar area, now incorporated into a greatly expanded Cadet Mess and Recreation Centre, is still known as 'Bill and Alfie's".

The Great War, the world's first industrial mass-war, was a global catastrophe that has given rise to a century of change, conflict and revolution. The title of Margaret MacMillan's recent book, The War That Ended Peace, says it all. We are still struggling with the War's consequences. Despite all the horrors of war it is perhaps fitting that one of the enduring Great War memorials to be found at the Royal Military College consists of two cartoon figures- symbols not of loss and grief but of the indomitable human spirit, the spirit that can triumph over adversity and that gives us hope for a better world.